Our History

From its creation until today, MBDA has always been at the forefront in imagining and designing cutting-edge and complex weapons systems, supporting the national sovereignty of its home nations and their allies.

Our History

1914-1945

First steps in the development of guided missiles

The concept of the remote-controlled aircraft emerged around 1900 from the convergence of aviation and radio. World War I led to several experiments carried by all the nations involved.

1945-1960

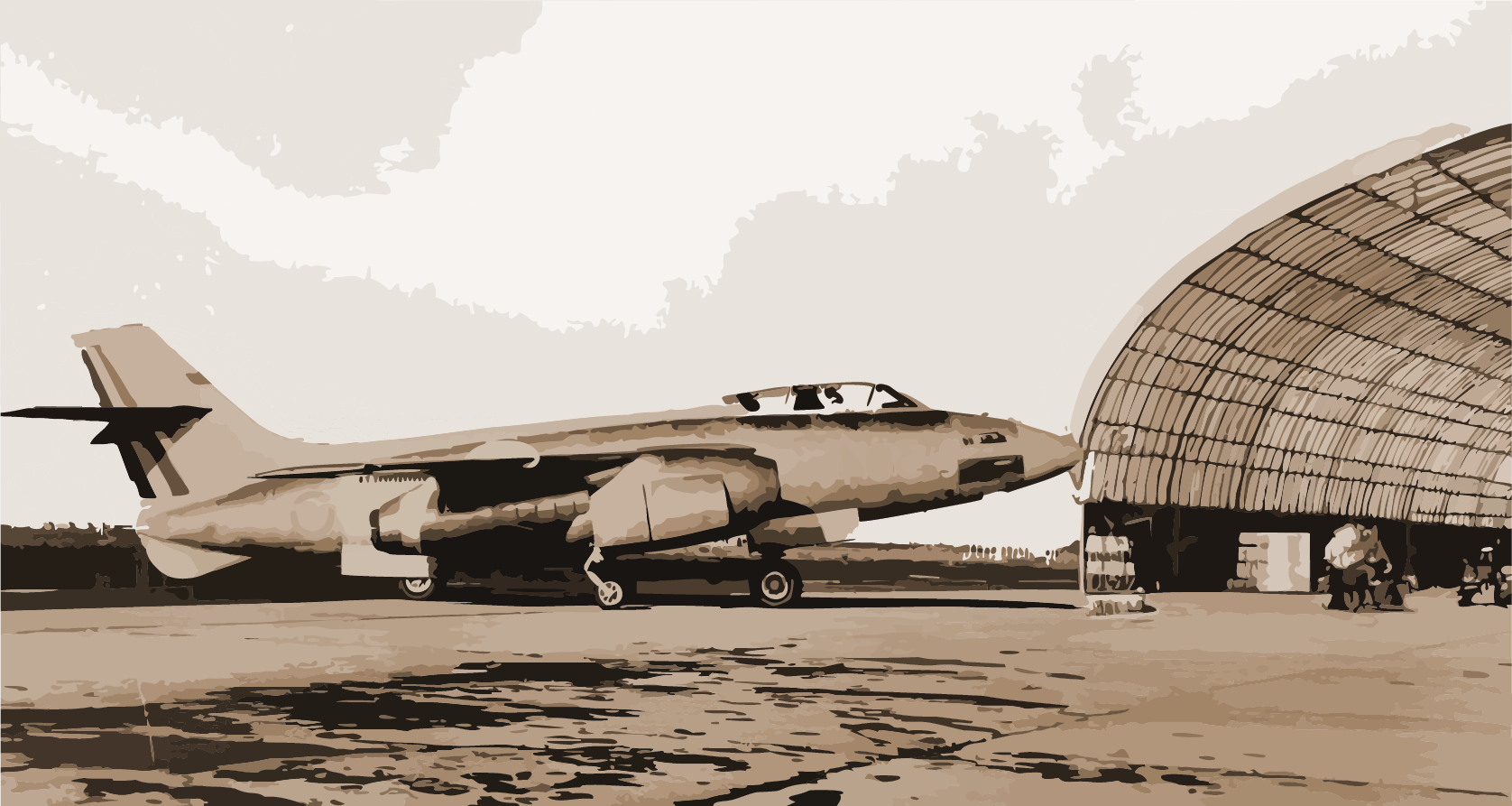

The pioneering period in the UK

The development of guided weapons had not been a priority during World War II, and for the major European leaders, the defence industry had yet to make up for lost time.

1946-1958

The pioneering period in France

The post-war era in Europe became a pioneering period for missile development, following the breakthroughs of the 1914-to-1945 timeframe.

1960-1967

Keeping pace

In the early 1950s, Europe played a pioneering role in the development of tactical missiles.

1971-1979

Europe reaches maturity

During the 1960s, the European industry went through a fast development and the decade ended in the co-operation and merging of leaders in the defence industry, compensating the fragmentation of research and production.

1980-1990

Modernisation of the European industry

The conflicts framed this time period, which could be considered to have set the scene for global modernisation of European defence.

1990-2002

A new landscape for co-operation

The 1990s started on a similar note as the context of the previous decade. Whilst the 1980s were framed by international conflict, the 1990s opened their own years with the Gulf War.

-

1914-1945

-

1945-1960 (in the UK)

-

1946-1958 (in France)

-

1960-1967

-

1971-1979

-

1980-1990

-

1990-2002